A story on Bloomberg with lots of interesting points:

"By Michael McDonald and Michael Quint

Dec. 24 (Bloomberg) -- Six years after embarking on an effort to lower borrowing costs using derivatives, New York is watching those savings evaporate.

The state( THAT'S CORRECT, THE GOVERNMENT BOUGHT SWAPS ) says it paid bankrupt( NOW YOU KNOW WHY THIS WAS A DISASTER. IT TRIGGERED A WHOLE INFINITY OF PEOPLE HAVING TO GET CASH. IT'S LIKE A BANK RUN ) Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. and other Wall Street banks at least $75.9 million since March to end interest-rate swap contracts that were supposed to lock in below-market rates. That money and the costs of issuing new debt to replace bonds linked to swaps( IN THIS ENVIRONMENT ) gone awry are eroding the $207 million in savings New York budget officials say the derivatives produced since 2002.

New York isn’t alone. Lehman’s bankruptcy filing on Sept. 15 triggered the termination of similar contracts across the country, forcing state and local governments and other borrowers in the $2.67 trillion municipal-debt market to buy out the agreements( PAY MONEY BACK ). They suddenly find themselves making unexpected payments at a time when their revenue is already under pressure from the worst recession since World War II ( A TERRIBLE TIME TO HAVE TO COME UP WITH CASH ).

“People are fixing problems right now,” said Nat Singer, managing partner at Swap Financial Group in South Orange, New Jersey, and the former head of municipal derivatives at Bear Stearns Cos. The number of new deals has shrunk to a “fraction” of the amount a year ago as issuers unwind failed swaps( BECAUSE OF THE BANKRUPTCY ) with Lehman, Singer said.

Bentley University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and a school district in Pennsylvania vowed never to use swaps again after losing money. The added costs in New York come as the state faces a record $15.4 billion budget deficit over the coming 15 months.

Lowering Costs

In a swap, parties agree to exchange interest payments, usually a fixed payment for one that varies based on an index. Borrowers may benefit by using swaps to lower interest expenses or lock in rates for future bond sales."

Here's a definition:

"An

exchange of

interest payments on a specific

principal amount. This is a

counterparty agreement, and so can be standardized to the

requirements of the

parties involved. An

interest rate swap usually involves just two parties, but occasionally involves more. Often, an

interest rate swap involves exchanging a

fixed amount

per payment

period for a payment that is not fixed (the floating side of the swap would usually be linked to another interest

rate, often the

LIBOR). In an interest rate swap, the

principal amount is never exchanged, it is just a

notional principal amount. Also, on a

payment date, it is normally the case that only the difference between the two payment

amounts is turned over to the party that is entitled to it, as opposed to exchanging the

full interest amounts. Thus, an interest rate swap usually involves very little

cash outlay."

And an example:

Copyright ®2004 International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc.

Alfa Corp Strong

Financial

Floating rate payment

(3-month Libor)

Fixed rate payment

(5% s.a.)

Terms:

Fixed rate payer: Alfa Corp

Fixed rate: 5 percent, semiannual

Floating rate payer: Strong Financial Corp

Floating rate: 3-month USD Libor

Notional amount: US$ 100 million

Maturity: 5 years

Interest Rate Swap example

• Alfa Corp agrees to pay 5.0% of $100 million on a semiannual basis to

Strong Financial for the next five years

– That is, Alfa will pay 2.5% of $100 million, or $2.5 million, twice a year

• Strong Financial agrees to pay 3-month Libor (as a percent of the notional

amount) on a quarterly basis to Alfa Corp for the next five years

– That is, Strong will pay the 3-month Libor rate, divided by four and multiplied

by the notional amount, four times per year

• Example: If 3-month Libor is 2.4% on a reset date, Strong will be obligated to pay

2.4%/4 = 0.6% of the notional amount, or $600,000.

– Typically, the first floating rate payment is determined on the trade date

• In practice, the above fractions used to determine payment obligations

could differ according to the actual number of days in a period

– Example: If there are 91 days in the relevant quarter and market convention is to

use a 360-day year, the floating rate payment obligation in the above example

will be (91/360) × 2.4% × $100,000,000 = $606,666.67.

A fixed-for-floating interest rate swap is often referred to as a “plain vanilla” swap because it is the most commonly encountered structure"

"New York agencies used them to lower the cost of almost $7 billion in bonds sold between 2002 and 2005, according to an Oct. 30 report from the budget division. The average fixed rate the agencies agreed to pay Lehman and other banks was 3.78 percent, compared with 4.5 percent if they had sold conventional tax-exempt debt( THEY GOT A LOAN AT LOWER INTEREST ), officials calculated.

The state failed to comprehend the extent of the risks( TOO MUCH ) involved in entering into the long-term contracts, which often last more than 20 years, the report said. They included the likelihood an investment bank would go out of business, triggering the termination of the agreement ( THAT'S IT ).

930,000 Contracts

“One of the main risks with swaps, which is that a sudden bankruptcy of a counterparty could terminate a swap in unfavorable mark-to-market conditions( CURRENT PRICES ), was not effectively addressed in the existing laws and agreements,” the budget division wrote in its annual report.

A budget-division spokesman, Matt Anderson, said in an e- mail that “given the current volatility in the market, we currently don’t anticipate entering into further swap agreements at this time.”

Lehman had about 930,000 derivatives( OH MY ) contracts of all types when it collapsed, according to bankruptcy filings. About 30,000 remain open( THAT'S NOT BAD WORK ), Robert Lemons, a Weil, Gotshal & Manges lawyer representing Lehman, said last week. The contracts are worth billions of dollars to Lehman’s creditors, though their exact value isn’t clear, he said.

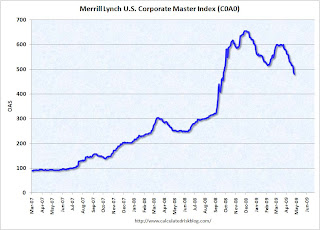

The cost of ending a contract depends on current interest rates. Since New York and other issuers agreed to pay a fixed rate to Lehman when borrowing costs were higher, they must pay the bank to end the deals( THAT'S IN THE CONTRACT ). The three-month dollar London interbank offered rate, or Libor, upon which many agreements are based has tumbled to 1.466 percent from 5.5725 percent in September 2007.

Swaps Approval

Because they are private agreements, no comprehensive data exist on how many municipalities( GOVERNMENTS ) are involved in the almost $400 trillion interest-rate derivatives market or the total paid to exit the contracts. Derivatives are contracts whose value is tied to assets including stocks, bonds, commodities and currencies, or events such as changes in interest rates or the weather( TRUE ).

New York passed a law in 2002 expanding the ability of state agencies and authorities to use swaps. It was signed by then-Governor George Pataki, a Republican. New Jersey, California and other states also use derivatives in their public financing.

Bentley University entered into swaps with Lehman and Charlotte, North Carolina-based Bank of America Corp. on $85 million of debt between 2003 and 2006. The school also had to pay a fee to end the swaps when Lehman collapsed, based on its contracts with the bank.

Upfront Cash

“It’s going to take awhile for people to get comfortable again, if ever,” said Paul Clemente, the chief financial officer at Bentley, who declined to disclose the amount of the fee. “As far as the future for interest-rate swaps, for me there is no future.”

Some borrowers also use swaps as a way to generate upfront cash, an attractive feature as the recession eats into municipal finances. At least 41 states and the District of Columbia face a combined budget shortfall of $42 billion this fiscal year, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, a non- partisan budget and tax analysis group, said Dec. 23. The estimate on Oct. 10 was $8.9 billion.

The Butler Area School District in Pennsylvania decided in August to pay JPMorgan Chase & Co. $5.2 million to back out of such a deal, more than seven times what it was paid to enter the agreement, rather than risk losing even more money over the 18- year contract. The district superintendent, Edward Fink, said he now thinks it’s inappropriate for school systems to dabble in such trades( NOT COMPETENT ), even though they were explicitly backed by the General Assembly in 2003.

Valuing Risk

JPMorgan said in September it would stop selling derivatives to states and local governments amid federal probes into financial advisers and investment bankers paying public officials for a role in swap agreements( COLLUSION ).

Borrowers “never put a value on the risks associated with the swaps( THE LENDERS SHOULD HAVE MADE IT PLAIN. THIS IS AT LEAST NEGLIGENCE ),” said Joseph Fichera, president of New York-based Saber Partners LLC, a financial adviser to corporate and public sector borrowers. They only estimated the savings investment bankers and advisers were telling them they would get, he said.

The use of swaps began faltering in February when the market for auction-rate securities collapsed. States, local governments and nonprofits sold about $166 billion of the debt, and as much as 85 percent of that was then swapped to fixed rates, according to Fichera.

Bond Insurers

The collapse of the auction-rate market left issuers such as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey paying weekly or monthly rates of up to 20 percent. The swap agreements failed to adjust to swings in the underlying variable rates, leaving New York and others exposed to higher borrowing costs.

Interest rates on other types of municipal variable-rate debt also rose this year as investors boycotted bonds backed by MBIA Inc., Ambac Financial Group Inc. and other insurers that lost their AAA ratings because of their expansion into subprime- linked credit markets.

Some borrowers entered into new swaps after Lehman’s collapse, agreeing to pay higher than market rates in exchange for upfront payments to help cover the termination fees they owed Lehman( INTERESTING ), according to Swap Financial’s Singer. London-based Barclays Plc, which acquired Lehman’s brokerage, is among the banks bidding on this business, he said.

“The combined message from all of that is you cannot have complete confidence in your counterparty,” said Milton Wakschlag, a municipal finance lawyer in Chicago at Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. “People will be taking a hard look at some of the conventions of the marketplace” after they finish cleaning up from Lehman’s bankruptcy."

I consider this negligence if the borrowers were not clearly explained the risk. You also see Fraud and Collusion in this post. Point taken.