"Can We Inflate Our Way out of this Mess?

Three ways the U.S. can decrease the level of nominal debt as a percent of GDP:

- Default (not going to happen... at least while we still own the printing press)

- Increase productivity (and GDP), while paying down or maintaining the debt load

- Inflate our way out of it (decreases the value of debt in real terms)

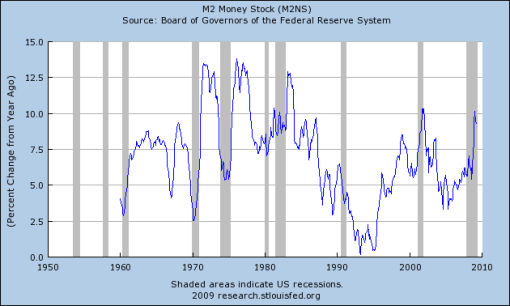

Of course, it can be done, but only for as long as the commitment to higher inflation is credible. Inflation is not some lightbulb that a central bank can switch on and off. It works through expectations. If the Fed were to impose a long-term inflation target of, say, 6 per cent, then I am sure it would achieve that target eventually. People and markets might not find the new target credible at first but if the central bank were consistent, expectations would eventually adjust. In the end, workers would demand wage increases of at least 6 per cent each year and companies would strive to raise their prices by that amount.Yves at Naked Capitalism agrees that it is a challenge, but possibly due to a different reason:

You may have noticed a crucial assumption...."workers will demand wage increases." Pray tell, how? Workers have no bargaining power in the US. Merely goosing interest rates does not a a tight labor market make.The key point is that in the current environment, workers have no power. While we all know about the spike in the unemployment rate, the other side of the story is the cliff dive in the number of new job openings. The odd thing is I first became fully aware of this information in Sunday's NY Times article Bleak Picture, Yes, But Help Still Wanted that made the case that the market was actually FULL of opportunity.

Stagflation was seen as impossible until it took place. I wonder if we could wind up with rising bond yields due to concerns about large fiscal deficits, with a lower rate of goods inflation due to the lack of cost push (wages are a significant component of the cost of most goods, save highly capital intensive ones). In fact, we could see stagnant nominal wages with mildly positive inflation, which means wage deflation. If that was also accompanied by high yields, you would have much of the bad effects of debt deflation per Irving Fisher (high real yields and reduced ability to service debt) since real incomes would be falling in the most indebted cohort.

Consider that in March, nearly 700,000 jobs disappeared. But now consider this: At the end of March, there were 2.7 million job openings. What tends to get lost in the data picture is that just as some companies are laying off workers, other companies are hiring. In fact, the business world is changing at such a dizzying rate that some companies are cutting and hiring workers at the same time.Uh.... no. 2.7 million is down from 4.8 million openings as recent as the Summer of 2007; when 6 million less people were unemployed. In other words, the number of job openings has halved, while the number of those unemployed has doubled. That is not "bleak"... that is frightening.

This in turn has pushed the number of unemployed, as a percent of job openings, up more than three-fold to 500%. Yes, for each opening... 5 people want that job. That my friends is why, as Yves points out, workers don't have ANY bargaining power.

Thus, the concern I have is that inflation won't be driven through via wage increases (where at least workers salaries are keeping up), but by a spike in the price of commodities. If inflation concerns = dollar concerns = commodity spike, then that impossible stagflation may be possible once again.

Source: BLS

Me:

Don said...

I think that defaulting on foreign debt is the easiest option politically,especially if you can convince your citizens that foreigners got you into your mess. Kind of like Ecuador today.Here, people would focus on China.

Inflation is problematic in that there will be losers in your own citizenry, and they vote.

Don the libertarian Democrat